Burke and Hare, Edinburgh’s most infamous duo, carved a bloody past through the city’s dark history. Auld Reekie has a magical charm with the old buildings and cobbled streets of the Old Town. However, this belies a dark and bloody history which was fraught with death, disease, poverty, betrayal, and downright brutality. From plague to the treachery of the Black Dinner, from the witch trials to the treatment of the Covenanters by Bluidy Mackenzie, from Rizzio’s murder to Deacon Brodie, Edinburgh’s past is steeped in violence and human suffering.

Burke and Hare murdered sixteen people in Edinburgh during 1828, selling their corpses to medical schools. This dark chapter in Scottish history arose as a result of desperation, greed, and scientific ambition.

The medical crisis of early 19th-century Edinburgh

Edinburgh became a leading European centre for anatomical study in the early 1800s. Consequently, the demand for cadavers rose sharply. However, the legal supply remained limited. Scottish law allowed bodies from people who died in prison, suicide victims, and unclaimed foundlings or orphans.

Meanwhile, medical teaching expanded. Anatomy lecturers needed fresh subjects for demonstration. In addition, students expected regular dissections as part of their training. As a result, a large and persistent shortfall developed.

The illicit body trade set up the perfect circumstances for Burke and Hare to operate

This shortage encouraged an illicit trade. Grave robbers, often called resurrection men, exhumed newly buried bodies and sold them to anatomy schools. Families pushed back. They did not want the bodies of their loved ones violated. For example, watchmen were hired, watchtowers were built, and iron cages called mortsafes were placed over coffins. Yet these measures also made bodies harder to obtain, which intensified the pressure on anatomists and suppliers.

Prices reflected the market. Corpses could sell for several pounds, with higher prices in colder months because bodies kept longer. Therefore, a single body could represent weeks or months of wages for labourers. This financial incentive mattered.

Who were Burke and Hare?

William Burke was born in 1792 in Urney, County Tyrone, Ireland. He later travelled to Scotland and worked as a labourer, including on the Union Canal. By 1827, he lived in Edinburgh and worked as a cobbler. Contemporary descriptions often present him as sociable and outwardly respectable.

William Hare was also an Irish immigrant, although details of his early life are uncertain. He ran a lodging house in Tanner’s Close, in the West Port area of Edinburgh. Reports describe him as rough, quarrelsome, and prone to violence. His partner, Margaret, helped run the lodging house. Burke lived with Helen McDougal, sometimes called Nelly.

Burke and Hare became friends after meeting through seasonal work. Soon, both couples were living in or around the Tanner’s Close lodging house. Drink and disorder were part of daily life, and the lodging house provided access to vulnerable lodgers and visitors.

Burke and Hare’s first sale: a death by chance

In late 1827, an elderly lodger named Donald died at Hare’s house owing rent. Hare and Burke decided to sell the body to recoup their loss. They removed the corpse from its coffin, filled the coffin with bark to disguise the weight, and then carried the body into the city in search of an anatomist.

They reached Dr Robert Knox’s premises in Surgeon’s Square. Knox was a prominent anatomy lecturer with a large student following. The pair received £7 10s for Donald’s body. For them, it was a striking sum. Importantly, they believed the door was open to repeat business.

Dr Robert Knox and Edinburgh’s anatomy trade

Robert Knox was a well-known anatomy teacher in Edinburgh. His lectures drew large audiences, and his courses promised demonstrations on fresh subjects. This demand made suppliers valuable. At the same time, the trade operated in a grey zone. Disturbing a grave was illegal, yet a corpse itself was not clearly treated as property under the law of the time.

Knox later insisted he did not know murder lay behind the bodies he received. Nevertheless, public anger focused on him. People asked why an anatomist would accept so many fresh corpses without questions. This tension, between medical need and moral responsibility, sits at the heart of the story.

From opportunism to murder

After the first sale, Burke and Hare did not immediately begin killing. However, in early 1828, a lodger became ill, and Hare feared sickness would drive away customers. Instead of waiting for a natural death, Burke and Hare suffocated the victim and sold the body.

They repeated the pattern. Victims were often lured to the lodging house, given whisky, and killed by suffocation. The method was quiet and left little visible injury, which made detection difficult with the forensic limits of the period. Later, the term “burking” came to mean killing by smothering to supply a body for dissection.

Victims and escalation

Over roughly ten months, at least sixteen people were killed. Many were poor, socially marginalised, or transient. This mattered because such people were less likely to be reported missing quickly, and less likely to trigger a sustained investigation.

Some victims are known by name. Abigail Simpson, a salt seller, was murdered in February 1828. Mary Paterson, a young woman, was killed in April after being plied with alcohol. Others included lodgers, elderly women, and people drawn in by promises of drink or shelter.

One of the most infamous victims was James Wilson, known as “Daft Jamie”, a recognisable young man with a limp and learning difficulties. His disappearance drew attention because people knew him. Reports indicate that some students recognised the body. Consequently, rumours spread rapidly, which increased suspicion around Knox’s dissecting rooms.

Margaret Docherty and discovery

The final murder, that of Margaret Docherty in late October 1828, led directly to exposure. Docherty, an Irish woman, was lured in with a story of shared origins and hospitality. She was killed in a lodging house where other lodgers were present nearby.

Two lodgers, Ann and James Gray, became suspicious when they were barred from approaching a bed where they had left belongings. When they searched, they found Docherty’s body hidden in straw. They reported the matter to the police, despite attempted bribery. Although the body was moved quickly to Knox’s premises, the discovery triggered arrests.

Investigation, trial, and the deal with Hare

A medical examination suggested suffocation was likely, but it could not be proven conclusively. Police suspected more murders. However, evidence was scarce because most bodies had already been dissected.

To secure a conviction, the Lord Advocate offered Hare immunity if he testified against Burke. Hare accepted and gave detailed statements about the murders. Burke and Helen McDougal were charged. At trial, Burke was convicted of the murder of Margaret Docherty. McDougal received a “not proven” verdict, meaning the case against her was not established.

Punishment and aftermath

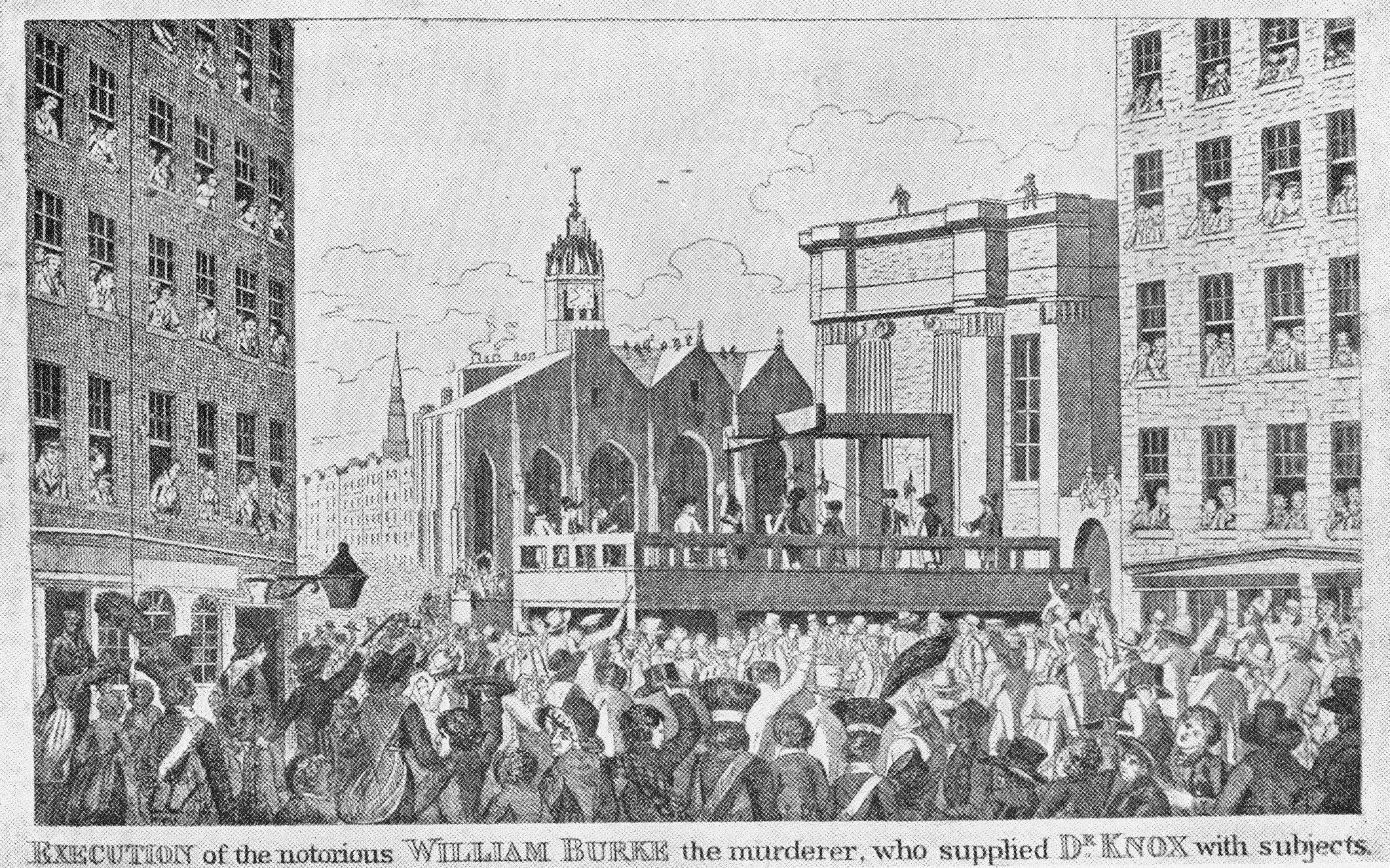

Burke was hanged on 28th January 1829. As part of the sentence, his body was publicly dissected. His skeleton was preserved and remains in Edinburgh’s medical collections. This outcome was widely seen as grim justice, given the nature of the crimes.

After his release on the 5th February 1829, Hare was reportedly blinded in a mob attack and ended his days as a beggar in London. However, more reliable accounts suggest he travelled to Dumfries before eventually returning to Ireland. Helen McDougal narrowly survived a similar confrontation before she fled to Australia. Maggie Laird also escaped the city and sought refuge in Ireland.

Knox was not prosecuted. A formal inquiry cleared him of knowing involvement. Even so, public opinion turned sharply against him, and his career in Edinburgh was damaged. He eventually left the city and worked elsewhere.

The Anatomy Act 1832

The Burke and Hare murders heightened public awareness of the cadaver shortage and the dangerous incentives it created. Over time, this pressure contributed to reform. The Anatomy Act 1832 expanded legal access to bodies for medical study, particularly unclaimed bodies from institutions, and helped reduce the market for grave robbing and anatomy murders.

The case also created a new word. “Burking” became a term for smothering murder. In Edinburgh the children sang a new rhyme:

Up the close and doon the stair,

But and ben wi’ Burke and Hare.

Burke’s the butcher, Hare’s the thief,

Knox the boy that buys the beef.

— 19th century Edinburgh rhyme